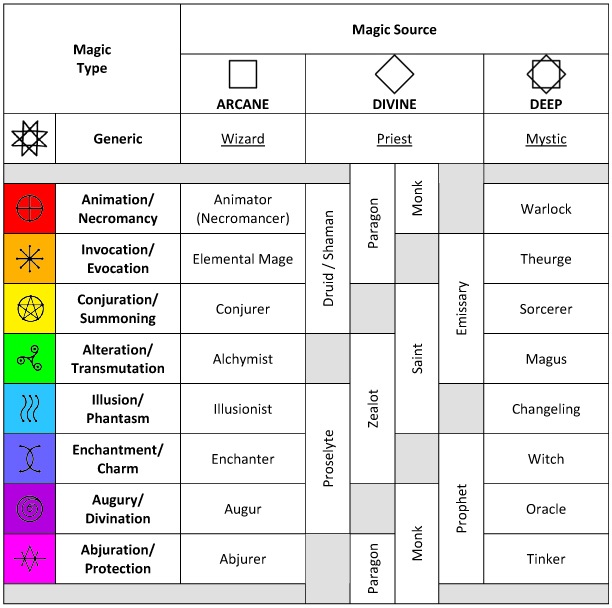

Now the rubber hits the road. Let’s look at class types for Wizards.

First off, I much prefer the term “Wizard” to “Mage” or “Magic User”. It’s got that certain old-school feel to it, and you know I’m OldSkool.

As a general class, Wizards are specialists in the use of arcane magic. They are the technologists and scholars of the supernatural. As such, intelligence is their prime attribute, and wisdom their secondary attribute. Unlike in the core rules, Wizards in this schema do not have any minimum ability stat requirements. However, low-intelligence or low-wisdom Wizards face many disadvantages and can be a threat to themselves as well as others. For specifics, see below.

Dealing in magic is dangerous business. Spells draw their power from planes of existence outside our own, and don’t follow our tidy physical laws. Learning and using magic requires strict discipline and care: even the most casual mistake and innocuous spells can drive you insane, take over your mind, kill you, or unleash unspeakable horrors. Wizards can gain access to unmatchable powers, but risk everything to do so. For this reason, as much as they may be admired for their accomplishments and power, they are also feared and reviled for the danger they present to everyone around them. Wizard pogroms are distressingly common. Thus Wizards tend to be somewhat secretive.

The master class template for Wizards applies to all sub-types that follow, modified only by the information provided for each sub-type specifically.

You may notice some changes with the level titles. These don’t get used a lot in real game play because the core rules titles don’t make a lot of sense. I’ve changed them to reflect a kind of pseudo-scholastic apprentice-master system by which Wizards organize and train themselves. Every Wizard except an Arch Wizard will have a higher-level teacher with whom they study/train and to whom they owe some sort of allegiance (and possibly tuition), whatever that may be. The student will always refer to their teacher as “master” regardless of the teacher’s actual experience level title, except that Grand Wizards, Grand High Wizards, and Arch Wizards are always referred to by their whole title (we doubt you’re on a first-name basis with the likes of them, anyway).

Wizards may not advance in level if they do not currently have a teacher. A wizard who finds him or herself without a teacher needs to find another one of sufficiently high level in the relevant area of specialty with a willingness to take him or her on as a student to allow further experience progress. To determine if a teacher’s level is high enough to allow advancement, take the character’s current level plus three (+3) until level 10, and from level 10 on, the current level plus one (+1). Note that this means a Wizard teacher of at least 12th level is required for promotion from Professor into the ranks of the full Wizards (from level 9 to 10).

Also, there’s probably an exam.

WIZARD

WIZARD

EXPERIENCE & LEVEL PROGRESSION (Chart 1)

NOTES for Chart 1:

* Player characters typically do not progress beyond 20th level, as their powers, responsibilities, and entanglements prevent them from doing much more than ruling their domains and settling squabbles among their clients and students. Higher-level Wizards are certainly possible, but nobody’s seen one in thousands of years (and thank goodness for that).

** “Wizard” is the generic title used by all Wizards above level 9. Specialist sub-classes will typically substitute the name of their specialty title in place of the generic (e.g. “Grand Necromancer” instead of “Grand Wizard”) or modify the generic with the color designation of their specialty (e.g. “Forauld, the Yellow Wizard”)

SPELLS KNOWN BY LEVEL (Chart 2)

A Wizard’s experience level determines the maximum spell level they are capable of safely knowing and using (i.e. putting in their head and thinking about).

| Exp. Level | 1-2 | 3-4 | 5-6 | 7-8 | 9-11 | 12-13 | 14-15 | 16-17 | 18+ |

| Max Spell Level | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

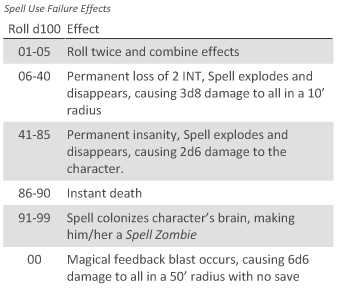

If a Wizard attempts to memorize, read, or use a spell of a higher level than they are “rated” for by experience level, the Wizard must save versus spell magic on every attempt (e.g. reading it, memorizing it, using it, or even forgetting it) with a penalty calculated as follows:

(Level of Spell – Max Spell Level allowed) x 3

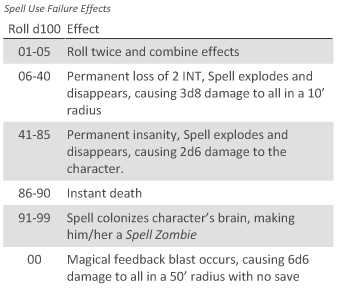

Regardless of penalty, a critical success (natural 20 on 1d20) on a saving throw always saves (see rule: Heroic Saves). Failing this saving throw will result in the following effect (roll 1d100):

SPELL MEMORIZATION

A Wizard can only know a spell if he or she has access to it in some written form and has made the effort and taken the risk to memorize it. All Wizards record their spells in spellbooks using Write Magic (see note below).

The number of spells that may be known (i.e. memorized, or contained within the head of the Wizard) is determined by the following calculation (all fractions rounded down):

Maximum Spells Known = {(INT-6) / 2} + Experience Level

So, for instance, if Forauld is Level 10 and has an intelligence stat of 13, he can have up to 13 spells memorized at any given time [{(13-6)/2)+10=13.5 rounded down to 13]. A Wizard may also know as many cantrips (minor magical tricks rather than major magical effects) as spells if cantrips are used in the campaign.

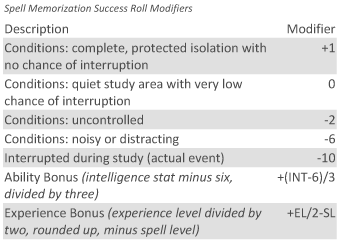

To memorize a spell requires both time and success roll, modified by conditions. Doing so is not just a matter of learning words and gestures in the correct order. Memorizing a spell involves imprinting the spell itself on the structure of the Wizard’s brain. The base time it takes to memorize any spell is the level of that spell in days. For instance, the base time required to memorize Dispel Magic (a 3rd Level spell) is three days. This assumes optimum conditions for concentration and study (a quiet, private place without interruption).

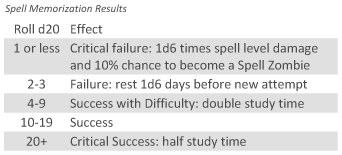

When attempting to memorize a spell, the Wizard must first determine whether or not he/she has a memory slot available to fill, the level of the spell to be memorized, the conditions under which the study is to take place, and then make a roll for success on the following table using 1d20:

The following modifications to the success roll for spell memorization should be observed:

It is not possible to memorize spells while engaging in other tasks. Obviously, trying to memorize spells in less than optimal conditions is something that should be carefully avoided. It’s also a very time-consuming process (it could take months for a high-level wizard to forget and re-memorize all his spells). Fortunately, once a spell has been memorized, it is not easily forgotten. Unfortunately, if you wish to forget a spell, a special effort must be made to do so, similar to the memorization process above. If all memory slots are full, a spell will have to be forgotten before a new one can be memorized.

SPELL CASTING & MANA

To cast a spell, it must be known (already memorized) and the Wizard must have enough available mana (magical energy) to power its operation. Mana is the underlying fuel for all magic. Without mana, magic doesn’t work. No matter how many spells you know, a lack of mana will leave you waving your hands around and mumbling for nothing.

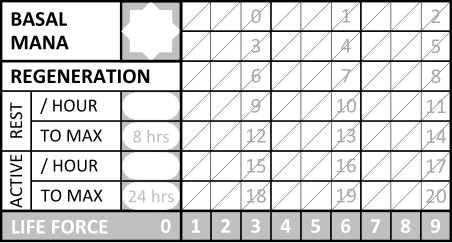

All living things generate mana internal to themselves as a renewable source of magical energy. The measure of how much mana a being generates daily and has available for use is called basal mana. Except for elves, most player character races generate three (3) basal mana points at level zero (without any further development and training). Through physical and mental training, Wizards are able to increase their basal mana reserves by three (3) points for each level as they increase in experience.

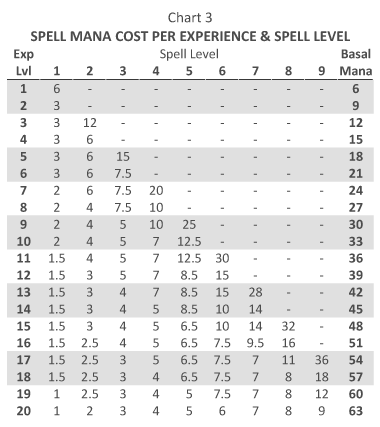

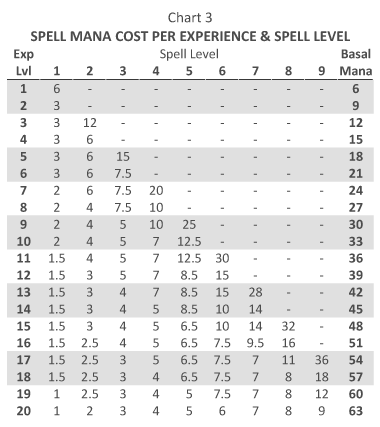

The cost in mana points to cast a spell depends on the level of the spell and the level of the caster, as illustrated in the following chart:

Up Next: Wizard Sub-Classes